Permanent magnets

Centuries ago, it was discovered that

certain types of mineral rock possessed unusual properties

of attraction to the metal iron. One particular mineral,

called lodestone, or magnetite, is found

mentioned in very old historical records (about 2500 years

ago in Europe, and much earlier in the Far East) as a

subject of curiosity. Later, it was employed in the aid of

navigation, as it was found that a piece of this unusual

rock would tend to orient itself in a north-south direction

if left free to rotate (suspended on a string or on a float

in water). A scientific study undertaken in 1269 by Peter

Peregrinus revealed that steel could be similarly "charged"

with this unusual property after being rubbed against one of

the "poles" of a piece of lodestone.

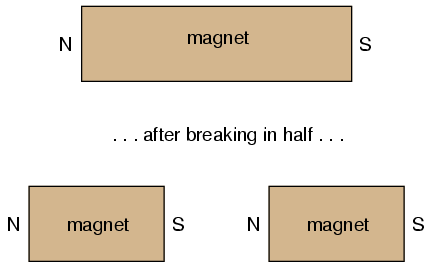

Unlike electric charges (such as those

observed when amber is rubbed against cloth), magnetic

objects possessed two poles of opposite effect, denoted

"north" and "south" after their self-orientation to the

earth. As Peregrinus found, it was impossible to isolate one

of these poles by itself by cutting a piece of lodestone in

half: each resulting piece possessed its own pair of poles:

Like electric charges, there were only two

types of poles to be found: north and south (by analogy,

positive and negative). Just as with electric charges, same

poles repel one another, while opposite poles attract. This

force, like that caused by static electricity, extended

itself invisibly over space, and could even pass through

objects such as paper and wood with little effect upon

strength.

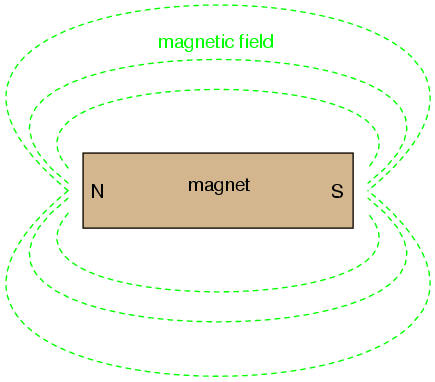

The philosopher-scientist Rene Descartes

noted that this invisible "field" could be mapped by placing

a magnet underneath a flat piece of cloth or wood and

sprinkling iron filings on top. The filings will align

themselves with the magnetic field, "mapping" its shape. The

result shows how the field continues unbroken from one pole

of a magnet to the other:

As with any kind of field (electric,

magnetic, gravitational), the total quantity, or effect, of

the field is referred to as a flux, while the "push"

causing the flux to form in space is called a force.

Michael Faraday coined the term "tube" to refer to a string

of magnetic flux in space (the term "line" is more commonly

used now). Indeed, the measurement of magnetic field flux is

often defined in terms of the number of flux lines, although

it is doubtful that such fields exist in individual,

discrete lines of constant value.

Modern theories of magnetism maintain that a

magnetic field is produced by an electric charge in motion,

and thus it is theorized that the magnetic field of a

so-called "permanent" magnets such as lodestone is the

result of electrons within the atoms of iron spinning

uniformly in the same direction. Whether or not the

electrons in a material's atoms are subject to this kind of

uniform spinning is dictated by the atomic structure of the

material (not unlike how electrical conductivity is dictated

by the electron binding in a material's atoms). Thus, only

certain types of substances react with magnetic fields, and

even fewer have the ability to permanently sustain a

magnetic field.

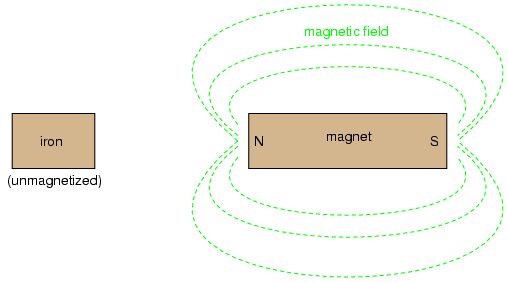

Iron is one of those types of substances

that readily magnetizes. If a piece of iron is brought near

a permanent magnet, the electrons within the atoms in the

iron orient their spins to match the magnetic field force

produced by the permanent magnet, and the iron becomes

"magnetized." The iron will magnetize in such a way as to

incorporate the magnetic flux lines into its shape, which

attracts it toward the permanent magnet, no matter which

pole of the permanent magnet is offered to the iron:

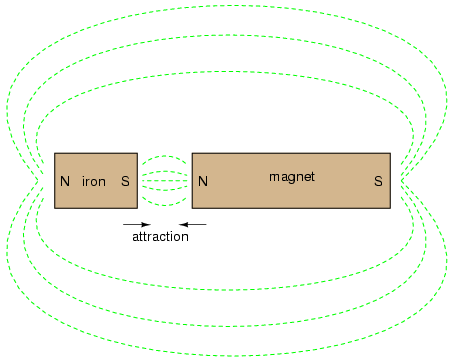

The previously unmagnetized iron becomes

magnetized as it is brought closer to the permanent magnet.

No matter what pole of the permanent magnet is extended

toward the iron, the iron will magnetize in such a way as to

be attracted toward the magnet:

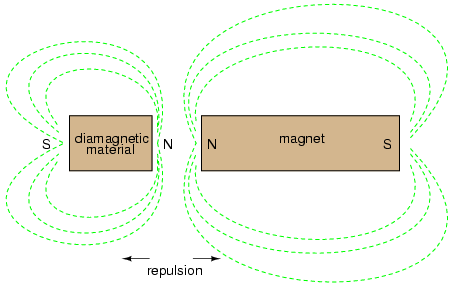

Referencing the natural magnetic properties

of iron (Latin = "ferrum"), a ferromagnetic material

is one that readily magnetizes (its constituent atoms easily

orient their electron spins to conform to an external

magnetic field force). All materials are magnetic to some

degree, and those that are not considered ferromagnetic

(easily magnetized) are classified as either paramagnetic

(slightly magnetic) or diamagnetic (tend to exclude

magnetic fields). Of the two, diamagnetic materials are the

strangest. In the presence of an external magnetic field,

they actually become slightly magnetized in the opposite

direction, so as to repel the external field!

If a ferromagnetic material tends to retain

its magnetization after an external field is removed, it is

said to have good retentivity. This, of course, is a

necessary quality for a permanent magnet.

-

REVIEW:

-

Lodestone (also called Magnetite)

is a naturally-occurring "permanent" magnet mineral. By

"permanent," it is meant that the material maintains a

magnetic field with no external help. The characteristic

of any magnetic material to do so is called retentivity.

-

Ferromagnetic materials are easily

magnetized.

-

Paramagnetic materials are

magnetized with more difficulty.

-

Diamagnetic materials actually tend

to repel external magnetic fields by magnetizing in the

opposite direction.

|